-

-

Jean-Pierre Pincemin was born on April 7, 1944, in Paris, during a harsh period in history. Of those early years of his life, Pincemin tells us little: "I was neither happy nor unhappy; I had an environment and not enough imagination to think of another one." And that’s about it—likely due to his reticence.

His move to Cachan and enrollment in a vocational school, where he prepared for a CAP (certificate of professional competence) as a turner, became the catalyst for a transformative encounter with the world of art and the arts. Encouraged by the enthusiasm of a drawing teacher for the great classical masters and art history, Pincemin began to visit the halls of the Louvre regularly. On Friday afternoons, taking advantage of—or sometimes creating—free time in his schedule, he would escape to Paris to lose himself among the great masters of painting. It was also during this period that he developed a passion for jazz, cinema, classical music, and modern art.

In Paris, always moving between the Louvre, the art galleries on the Right Bank, and the more avant-garde galleries on the Left Bank, he met Jean Fournier, a gallerist who championed a new generation of French artists (the B.M.P.T group). These artists sought to eliminate any notion of figures or representation in painting, stripping it of all symbolic forms by using predefined and automated graphic processes. Fournier and Pincemin immediately forged a strong bond of complicity.

-

JEAN-PIERRE PINCEMIN

Sans Titre (Carrés Collés), 1973Toile découpée, teintée et réassemblée / Cut, dyed, and reassembled canvas

279 x 371 cm / 109 7/8 x 146 1/8 in.

-

Jean Fournier, to whom Pincemin showed his early works, encouraged him to continue his aesthetic explorations, telling him that he was meant to be a painter. “I took that very seriously,” Jean-Pierre Pincemin would later admit. It was around this time that Pincemin began creating his *Carrés-Collés* (Glued Squares). Based on a predetermined system of composition, he would cut pieces of salvaged canvas, dye them (he preferred dye to paint until the early 1970s), and then assemble them according to the pre-established pattern. The reconstructed canvas was left free, untethered. This method, in which the automatism of the gesture combined with the repetition of preconceived sequences and the randomness of how the dye soaked into the fabric, closely paralleled the explorations of American minimalist artists of the time, as well as the French avant-garde artists championed by Jean Fournier. These artists shared a common goal: challenging the traditional conception of the canvas as a support, questioning the hand/brush relationship, and thereby distancing the painter’s direct touch while deconstructing the spatial composition of the pictorial surface.

Pincemin's name is often associated with *Supports/Surfaces*. While he interacted with the artists of this "group" (which, in fact, was not a formal group) and participated in some exhibitions, his involvement in *Supports/Surfaces* was quite marginal.

"Supports/Surfaces" was a generation of artists in the late 1960s exploring a novel artistic approach that balanced tradition with an understanding of the influence of the New York School and American abstract expressionism, which had recently disrupted the European—and particularly French—art scene. By deconstructing the traditional concept of painting—removing the canvas from its stretcher, abandoning the brush, distancing the artist’s hand, and thus the expressiveness of the creator—these artists sought to reinvent the act of creation. "The object of painting is painting itself, and the works exhibited refer only to themselves (...). Hence the neutrality of the works presented, their lack of lyricism and depth," they declared in 1969.

Pincemin, self-taught and more inclined toward practice than theoretical or aesthetic debates, found great pleasure in the act of painting. From 1970 onward, he continued the research he had begun with the *Carrés-Collés*, simplifying the principles of constructing the overall schema, which gave rise to what became known as the *Palissades* (Fences). Long, wide strips of canvas were cut, painted, or soaked in baths of paint—a technique he increasingly adopted—and then assembled in an orthogonal pattern, creating the appearance of a fence. The work on color, texture, and interplay of density, shine, and reflections carried, in the precise words of Philippe Dagen, “too much exposed voluptuousness, too much sensuality in the handling of the material (as one might say ‘working the body’),” to align with the ideal of deconstruction or "anti-painting" advocated by *Supports/Surfaces*.

-

-

In his works from the 1970s, composition and color form the two structuring poles of his paintings. The orthogonal division of these works brings great stability to the painted surface. The strips of canvas, assembled with glue—often black—create outlines that define each formal unit and contribute to an almost architectural whole. “The canvas is, a bit like in 15th-century Italian painting, a small piece of architecture with a top and a bottom.” This focus on the construction of pictorial space is a central element of his aesthetic explorations. While this aligns with a staging of pictorial signifiers (format, support, surface, color, gesture) reminiscent of the concepts he engaged with during his *Supports/Surfaces* years, it is also a clear demonstration of the importance he places on the ordering of the canvas’s space: well-defined and organizing the color within it.

The monumental quality of his work exerts a physical impact, weighing with its full pictorial space on reality and giving color the room it needs to assert its presence. This presence is revealed—never flat but always highly worked. Deep colors, drawn from the very fiber of the canvas, are achieved through a process of successive dye baths. Dark underlayers allow him to play with density, creating effects of transparency and texture.

-

-

The division in Pincemin's compositions can be seen as a kind of cadastre. Initially a *physical* division, achieved through strips of canvas that were cut, painted, and assembled, it became a *graphic* one starting in the late 1970s. These works, now painted on stretched canvas, were structured by an orthogonal design whose preparatory studies were carried out on graph paper. Within these parallelepipeds, the internal surfaces were infinitely modifiable, and the exact proportions of the whole could be transposed to other formats.

-

In 1984, Jean-Pierre Pincemin began experiencing health issues that required several hospital stays. These were "small misfortunes," as he described them, but they had a significant impact: "After such a long absence, I didn’t feel capable of painting as I did before." Something was stirring in the intimate process of Pincemin’s creativity, something that would profoundly redefine the nature of his work.

-

-

As we’ve seen, Pincemin’s compositions had until then been grounded in the use of the grid—a fundamental framework that provided his works with an unshakable stability and lent them a timeless abstract dimension. However, starting in 1979, Pincemin began to challenge this grid. It was engraving—a technique in which he was entirely self-taught—that became the tool for these explorations.

“Engraving came at the moment when I stopped being an analytical painter. I was searching for both a new medium that would allow me to escape the rigidity of the geometry so present in my painting and a reflective element to use in making engravings,” he explained. Aware of the repetition inherent in geometric invariance, passionate about painting, endlessly curious, and always seeking new discoveries, Pincemin felt the urge to explore other paths.

Freed from the constraints of color, form was liberated. Methodically and patiently, Pincemin experimented, playing with the new possibilities offered by this technique. Having previously subordinated line and color to the orthonormal grid, he now broke it apart. Gradually, straight lines became irregular, transformed into diagonals, and finally arabesques. From engraving, Pincemin drew a new repertoire of forms, a jubilant exploration of images of all kinds.

-

-

Continuing his exploration of figurative forms, religious subjects began to appear in Pincemin's work as early as 1988 (Mary Magdalene, Saint Christopher, Saint Roch, Saint Radegonde, and others). Once again, engraving served as a research tool. For example, there is a 1992 engraving in which Pincemin depicts himself as Moses, face-to-face with Saint Peter, in a composition directly inspired by an engraving by Jean Duvet (1485–1560), known as the Master of the Unicorn. Ten years later, this engraving was reinterpreted in painting (*Untitled (Moses and Saint Peter)*, 2002, 127 x 88 cm): an assistant projected the engraving onto the canvas, and the reversed drawing was traced. This method of projecting slides onto a canvas and enlarging the contours to transfer them became a common technique for Pincemin.

Like a jazz musician, Pincemin used a theme (the original engraving) and reinterpreted it with variations. These "themes," whose repertoire forms a body of work, are particularly evident in what he called his *"pocket museum"*: over time, Pincemin built a collection of small-format works, reductions of his favorite paintings.

-

The exhibition *"L’Année de l’Inde"*, held from January 28 to February 18, 1987, at the Galerie de France, demonstrated the breadth of evolution taking place in Jean-Pierre Pincemin’s studio. The 15 canvases on display, each approximately 2 x 2 meters, clearly marked a shift from pure abstraction to figurative work. Pincemin drew on the iconography of Indian folklore—which, that year, was the focus of cultural exchanges with France—as his first repertoire of forms explicitly interpreted in painting (elephants, trees, leaves, waves, birds, stars, etc.).

This figurative inclination, however, was not a turn toward "illusionism." With thick textures, schematic figures sketching images, and the freedom of his color choices, Pincemin's forms never sought to replicate reality. Instead, they clung to it, opening windows to an overflowing imagination. “My challenge has always been to achieve a balance on the surface of the canvas between the presence of an image and its absence, a proposal that can be recognized but whose identification is also disrupted,” he explained.

-

From 1986 onward, Pincemin's painting achieved absolute freedom. "The painter’s gaze has settled, once and for all, on the hope of a salvaged dimension of painting, on the understanding of forms, their inference and occurrences," and his creativity multiplied. At last free of theoretical or practical constraints, he embraced an unfettered artistic expression. Sculptures, engravings, drawings, paintings—his forms, compositions, and techniques all became testaments to a jubilant creativity. He used a mix of pigments, varied colors—sometimes salvaged—glue residues, car paint, and other “found colors,” as he called them. These elements, part of a "science of matter," revealed an artisanal approach, particularly evident in his sculptural work.

After *"L’Année de l’Inde,"* while his motifs diversified considerably, Pincemin did not abandon abstraction. Tripartite compositions reappeared regularly, with variations in format, as well as new abstract works featuring squares or circles. These compositions retained the spirit of construction and the flat, architectured surface that had characterized his *palissades* and three-band works. They also demonstrated a pronounced interest in colorimetry: the spectral distinction of color defined by hue, saturation, and luminance.

-

-

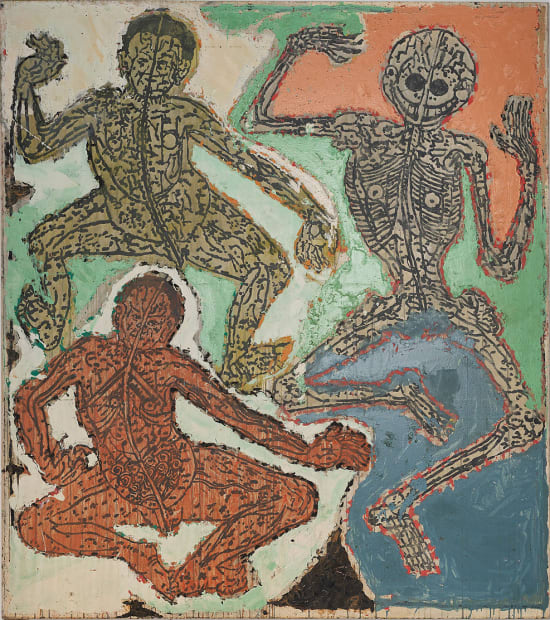

In the 1990s, an array of subjects began to emerge in Pincemin's work: *Creations of the World*, *Danse Macabre*, *Tiger Hunts*, and even erotic themes. This diversity of influences—including classical religious iconography, exotic representations such as Byzantine-inspired depictions of the Virgin Mary, as well as imagery from India (bestiaries, floral elements, etc.)—contributed to a reinterpretation of subjects from the classical iconography of European art history, as well as motifs from foreign cultures. Like many painters of his generation, Pincemin directly referenced the old masters, breaking down any notion of a strict division between modern art and classical art. His insatiable curiosity and his desire for freedom and exploration refused to conform to any set boundaries.

This interest in the history of representation and his unrestrained exploration of established schemas in his artistic practice reflected Pincemin’s vast curiosity and his intimate need for formal renewal. “The principle of discovery that I adopt is the hope for renewal and invention. This practice has the advantage of resisting rhetoric, of fixing nothing. The painter is ‘naïve,’ absolved, and without merit. Dissatisfied, he moves on to other preferences, speculating on the chances and surprises that such arrangements may offer us” (Paul Valéry).

-

-

Until the final years of his life, he experimented tirelessly, always, relentlessly. These back-and-forth movements between abstraction and figuration, and the abundance of subjects and techniques, greatly unsettled the public. While he had achieved significant notoriety in the latter half of the 1970s, the multiplication of his work in the early 1980s and his departure from strict abstraction surprised, even perplexed, some observers. A provocateur with what Jean-Marc Huitorel called an "uncompromising nonchalance," Pincemin stated in 1986: "We must change; we cannot continue doing the same thing indefinitely."

This is precisely where one of the keys to his work lies: his courage, his freedom, his almost audacious refusal to be confined by any artistic framework or style. Pincemin was an explorer, navigating freely, and always taking immense pleasure in painting and creating: “I cannot imagine doing without painting as a space of delight.” Pincemin’s art belongs to the universal mythology of the artist. At a time when many young artists aligned themselves with surface phenomena, joined schools or groups, and embraced theories, Pincemin was guided solely by the strength of his inner self and the jubilant pleasure he found in creative practices.

Far from reflecting ephemeral artistic systems, his work, tied to an eternal creative essence, carries within it all the images of a memory—images both inexplicable and self-evident. These images, gathered here and there and collected through his explorations, seem to embody André Breton’s advice: “Let go of everything. Let go of the prey for the shadow. Let go, if necessary, of an easy life, of what you’re given as a secure future. Hit the road.” And Pincemin, too, set out to explore the mysteries of art and to grasp the indescribable joys that these paths offer to curious minds.

ART GENÈVE 2025: JEAN-PIERRE PINCEMIN

Past viewing_room